In the early 1900’s, activists imagined a future flush with the fruits of innovation: machines would perform much of the most difficult labor, and the average person would work only four or five hours a day. While this vision didn’t quite materialize, the fifty or so years that followed saw wages grow and working hours shrink, as industrialization spread across the country and brought with it never before seen luxuries and conveniences.

The Best Laid Plans

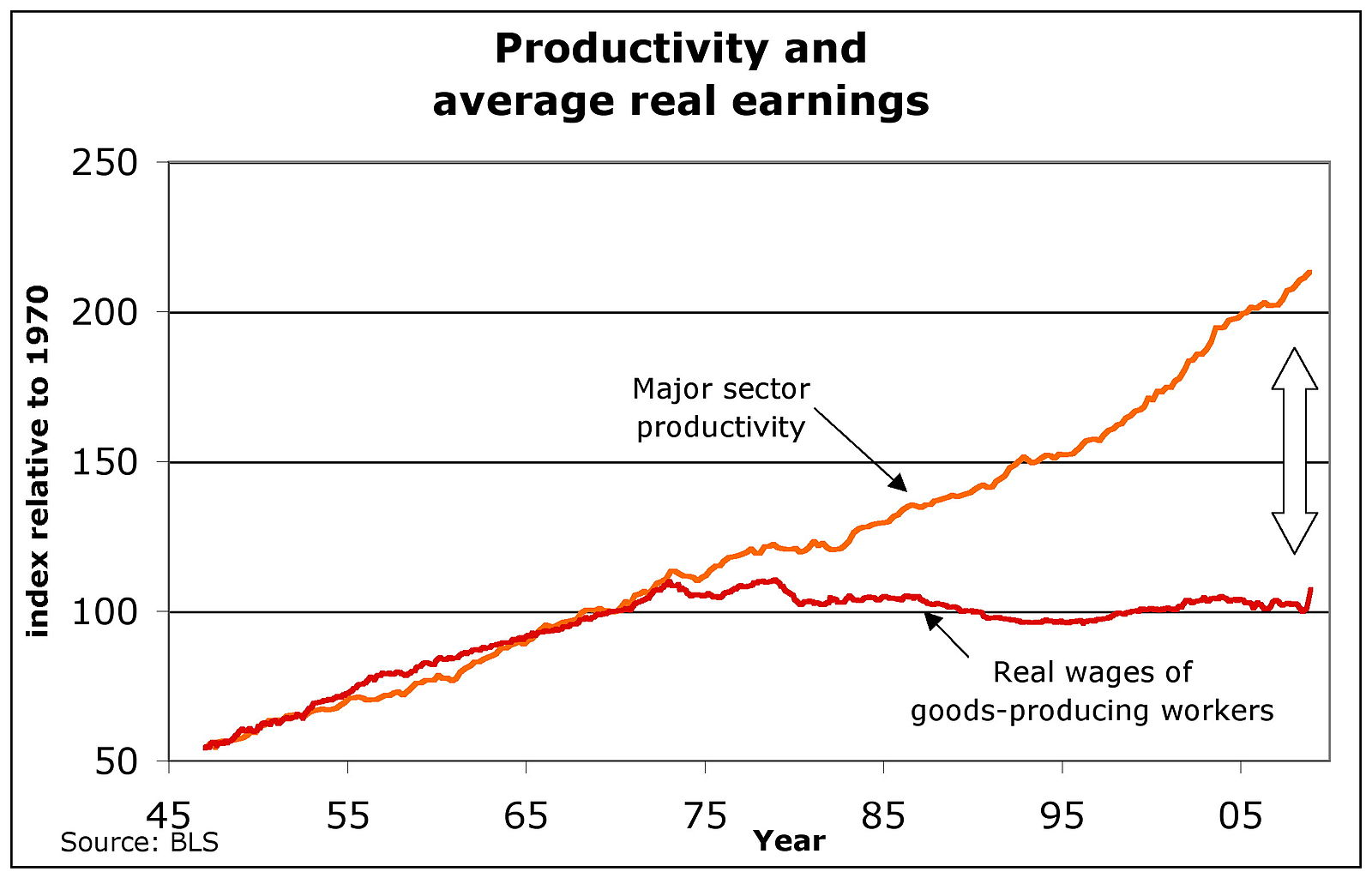

Yet since the 1970’s, productivity has continued to skyrocket but the average person’s living standards have stagnated. The past forty years have seen some of the most dramatic technological innovations in history — the internet, in particular — which have enabled workers to accomplish much more work in the same amount of time. So why, then, haven’t hours continued to shrink? Or, in the same vein, why haven’t wages at least increased to compensate workers for the more complex tasks they are performing? We sat down with Professor Joe Varga from the Labor Studies department to try to understand some of the roots of this dream denied.

Deskilling

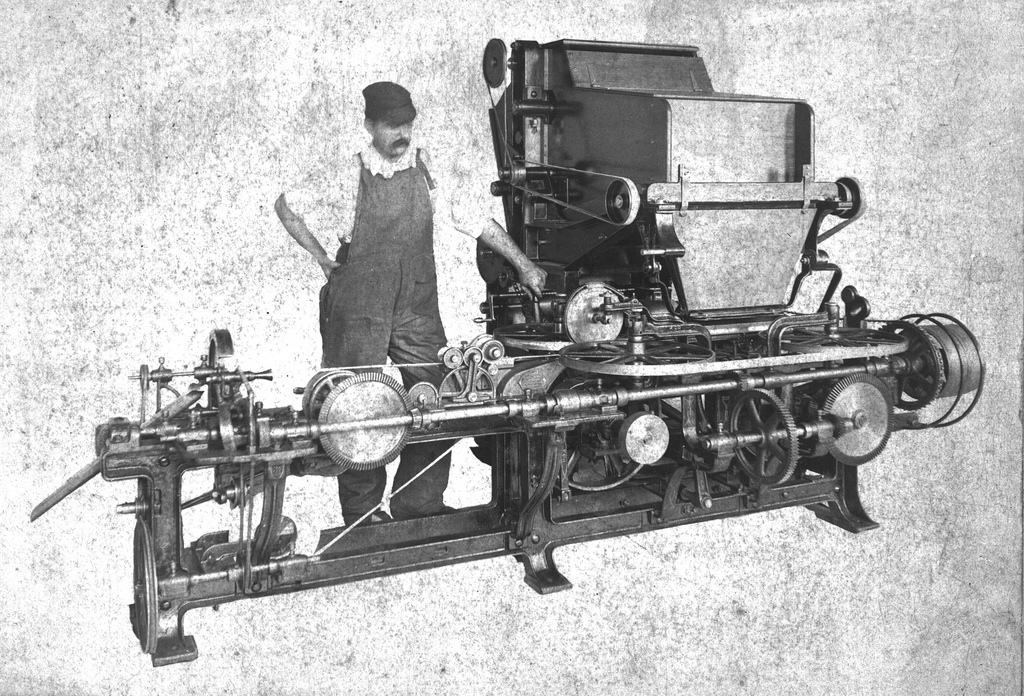

In Professor Varga’s eyes, one of the central processes of labor history over the past few centuries has been the idea of deskilling: the process by which a skilled job, through automation or some other process, becomes an unskilled one that anybody could perform.

For example, in the distant past, cigarette rolling was a highly specialized task that was handsomely compensated. However, cigarettes were also one of the first products to have their manufacture automated, and soon enough machines were turning them out by the thousands. In the end, while industrialization vastly increased the number of cigarettes produced, it ended up destroying an artisan craft passed down for generations. And without the uniqueness of their talents, most former cigar rollers lost their market power to fight for a good quality of life.

“That skill that they had was their bargaining chip,” Varga says. When cigarette rolling became automated, somebody who had that skill found their life more difficult, not easier, because their skill and thus their labor was less highly valued.

Labor Power

Is there any way for both workers and entrepreneurs to benefit from technological progress? One of the hallmarks of 20th century labor history was the rise of labor unions, which serve as a collective voice for workers trying to communicate their needs to management. The motivating aspiration behind collective bargaining is that, while a single worker who demands a pay raise or extra precautions against dangerous conditions might be fired, if a company’s employees express their demands as a united body then conditions that are beneficial to both labor and management can be found.

When Professor Varga was younger, he worked as a trucker and was a member of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Now that he studies labor history, he sees unions as a net benefit for an industry’s workers. “There’s no doubt; it’s called ‘the union advantage’, and you’ll actually see it in sectors,” Varga says. When a large portion of the workers in any given sector has unionized, that labor market power allows them to push the equilibrium wage up, which even benefits the workers in the sector who are not unionized. (A left-leaning economic policy organization recently published a study to this effect.)

However, Varga also points out that these higher wages can at times make our workforce less competitive with other countries’. “One of the reasons why General Electric moves its production facilities to Mexico is because [American workers] got to $27 an hour by having the power to bargain and negotiate it.”

Another potential downside of unions is that they tend to compel industries to hold on to jobs that might be better-suited to automation. One of the key aims of labor unions is to “de-commodify” labor, to see workers as humans rather than a cost to be optimized. As a result, they tend to strongly oppose suddenly cutting jobs that could be automated, jobs Varga says are often called “redundant” by companies. Many unions strive to protect these jobs during a transitional period during which workers are educated to work with new technologies. The downside is that people work hard performing tasks that might be completed more cheaply and efficiently by computers or robots, but at least they’re able to keep putting food on their table and maintain some sense of constancy in an ever-changing world.

Social stability is probably the most potent argument for balancing labor market relations.

Joe Varga

All in all, Varga says, this “social stability is probably the most potent argument for balancing labor market relations.” While it may be inefficient from an economic point of view to concentrate labor market power in the hands of workers, it is also inefficient for already-successful companies to dictate the terms of employment. There is a real human cost to the jobs lost and hours reduced due to automation, and its profits often benefit those with the money to capitalize on it rather than those adversely affected.

According to Varga, many workers would say “their communities were much more stable in the fifties through the seventies when those wages were higher and the jobs were guaranteed.” (Private sector union membership peaked at around 40% of the workforce during the 1950s.) By concentrating power in the hands of workers, unions — at the cost of some efficiency losses — have been able to ensure a high quality of life for many working people in the United States.

The Role of Technology

As globalization continues, collective bargaining becomes less and less effective, simply because workers in developing countries such as Russia or Turkey have very different needs than workers in wealthy countries like South Korea or the United States. But this isn’t the only reason that workers are not experiencing the lives of luxury imagined at the beginning of the last century.

As technological innovation accelerates, the skills workers need to succeed in the workplace change faster and faster. What’s more, workers are generally expected to grapple with these changes themselves. “That was not always the case,” says Varga. “G.E. used to train their workers for the newest machines that were coming in and we’ve lost that.” Instead, workers generally pay their own way through programs at community colleges like Ivy Tech, where they are able to learn many of the latest skills in two-year programs costing around $3000.

The difficulty, Varga says, is that in the worst cases “they come out of this two-year program and those skills are already obsolete. Or if they’re not obsolete, they paid $3000 for that training and they’re coming out to a job that only pays $11.50.” With such wages, unlucky workers have no choice but to work grueling hours to provide for their families, if they can even find a job. While Varga has only good things to say about Ivy Tech, he recognizes the huge challenge it and other training programs face in educating workers not for the technologies of today, but for the technologies of the future.

“We work all the time,” says Varga. “Our work is with us all the time.”

As these new technologies develop and unlock greater productivity for the workers who develop and operate them, they also often make it hard to draw the line between work and leisure, even for the more privileged workers in the information economy. “We work all the time,” says Varga. “Our work is with us all the time.” While Varga enjoys his work immensely, he says, “there is no point in my life where I don’t bring my work with me.” Computers enable workers to accomplish far more, but in doing so they often prevent them from taking the time to live their lives. “We should have been building towards this leisure society and instead we seem to be going into the offices,” says Varga.

Reaching for Tomorrow

While the development of computers has made the skills of those who work in the realm of ideas more valuable, many thinkers fear that developments in artificial intelligence will soon threaten even those workers.

This threat is taken so seriously, Varga reports, that it’s actually called “the elephant in the room” by labor theorists. The conventional wisdom among scholars in labor studies is that any work we know of today — even in highly specialized fields like law or medicine — will someday be better performed by artificial intelligence and robotics. In other words, the idea is that every job from flipping burgers to writing articles like this one will eventually be taken over by computers.

If that is the case, our society clearly has some thinking to do about the central way we currently see work as fitting into people’s lives. While in the present day technological advances have accompanied increased hours, in the long run a lot of people are going to be out of work. One of the solutions that has been proposed for this eventuality is what’s called a “universal basic income.” The idea behind a basic income is to take shared social resources, such as profits from oil reserves or cost savings from new technologies, and distribute them more evenly among the members of the population so that, Varga says, “they’re not completely threatened by technological advances.”

To move towards a universal basic income, though, we have to examine how our current economic system revolves around what Varga calls “the circulation of investment capital.” In a capitalist society, new and efficient methods of production are invented in order to reduce costs and yield profits to their inventors. If people don’t need to work for their money, where is the incentive to contribute to society, to make the world a better place? In Varga’s mind, “a lot of people would say the real problem is so many people are invested in this system of circulating investment capital and can’t think of anything else.”

What could a social framework to replace capitalism look like? Professor Varga’s partner teaches in the English Department and studies utopian and dystopian science fiction. “I think the answers are there,” says Varga. “I think the answers are in the visions that we’ve gotten from that literature, because it really is amazing: if you look at sci-fi from the early 20th century, it actually is predictive of where we are now and this science fiction that we’re reading now, it’s probably predictive of where we’re going in the future.”