In the 1940s, the world witnessed what may well be the most boring experiment a subject has ever participated in. In this elaborate study, subjects performed a variety of mental tests before and after multiplying 4-digit numbers in their heads for 12 hours straight. As if this wasn’t bad enough, they were then expected to come back for the next three days to do exactly the same thing (Huxtable et. al, 1945).

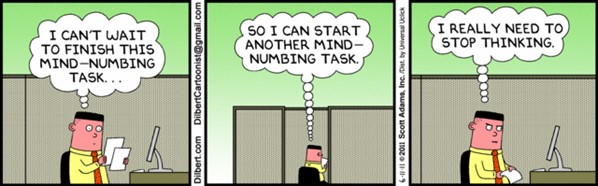

While most modern studies don’t reach quite that level of lassitude, many remain anything but exciting. This presents a problem, as these boring experiments come riddled with troubles.

When Nederkoorn and colleagues asked subjects either to do nothing or to press a button and receive a painful shock, subjects shocked themselves over and over, preferring pain to boredom (2016). And it’s not just that subjects don’t enjoy being bored. As boredom levels increase, attention is also negatively affected. At the same time, a host of positive factors—including intrinsic motivation, effort and self-regulation—decrease (Pekrun et. al, 2010). When we bore subjects, they exhibit each of these effects, resulting in lower-quality data. Everyone loses.

If boredom works its way into psychological studies, we’re toast. How can we make our experiments more enjoyable — or at least less boring? Here are three techniques to consider as you develop your studies.